To Buy or Not To Buy: A Checklist for Assessing Mergers & Acquisitions by Mauboussin M., Callahan D. & Majd D.(2017) — Credit Suisse

Executive Summary

Michael Mauboussin is a Managing Director and Head of Global Financial Strategies at Credit Suisse. He is the author of three books: The Success Equation, Think Twice and More Than You Know. He is also the author of numerous research papers. In this paper, the authors go over an empirical analysis that shows that M&A creates value in the aggregate, but that the seller tends to realize most of that value. They then develop a systematic framework to assess mergers and acquisitions by asking these four questions:

- How material is the deal?

- What is the market’s likely reaction?

- How did the buyer finance the deal?

- Which strategic category does the deal fall into?

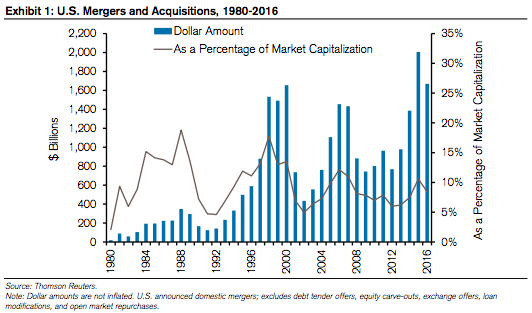

The M&A Market Dynamic

The M&A market tends to follow the stock market closely. As shown in the graph below, more M&A activity is generated when the stock market is up.

Given that companies tend to do more M&A when the market is expensive, it is challenging for them to generate high returns. At the end of business cycles, cheap and accessible financing tend to push firms to do larger deals at generous valuations as we saw with PE firms doing big buyouts during the top of the market in 2006, 2007 and subsequently failing to earn high returns. Thus, buyers early in the business cycle enjoy a larger pool of targets at cheaper valuations which help them generate higher returns from their acquisition.

The Checklist for Assessing M&A

1. How Material is the Deal?

The authors state that “the first question is whether the deal is likely to have a material impact on shareholder value.” This can be calculated through the Shareholder Value at Risk (SVAR) which measures the percentage of the firm’s value at risk in the event that synergies don’t materialize.

The SVAR is calculated by determining the premium paid by the buyer and how the buyer will finance the deal. For a cash deal, the SVAR is the premium divided by the market capitalization of the buyer. For a stock deal, the SVAR is the premium divided by the combined market capitalization of the buyer and seller with the implied premium. A low SVAR may suggest limited upside or downside for the buyer while a high SVAR may suggest large upside or downside for the buyer.

2. What Is the Market’s Likely Reaction?

The key question is whether the buyer gets more than it pays for. The authors present a simple formula in order to determine whether this is the case or not. The deal creates value for the buyer only if the synergies exceed the premium paid.

Net Present Value of the Deal for the Buyer = Present Value of the Synergies — Premium

Synergies

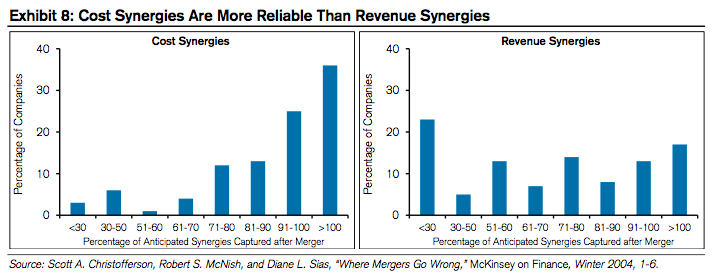

Research shows that cost synergies are easier to achieve than revenue synergies. Cost synergies are achieved when companies remove redundancies whereas revenue synergies are achieved because of the increase in sales from combining the businesses. Cost and revenue synergies are what we call Operating Synergies. Other forms of synergies, such as Financial Synergies, have played a less substantial role in the history of M&A deals. Aswath Damodaran wrote a more extensive paper on how to value synergies that we will explore in the near future.

Premium

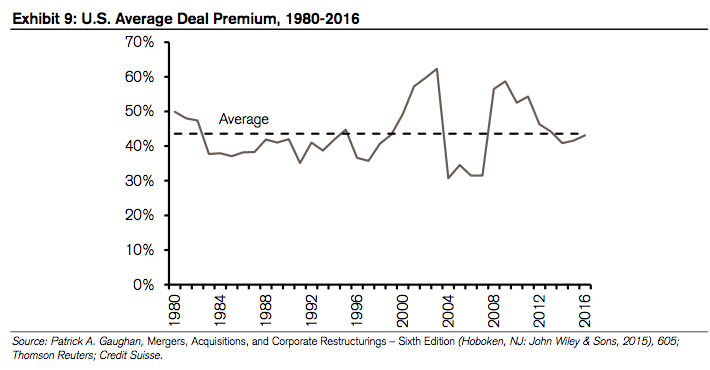

The premium is the difference between the price a buyer is willing to pay and the market price as determined by either private or public business valuation. As of 2016, the average premium is 43%. As a reminder, the larger the premium the buyer offers, the greater the synergies need to be achieved in order to create value.

3. How did the Buyer Finance the Deal?

Regardless of the way the buyer finance the deal by either cash, stock or a combination of both, in general, the market tends to responds more favourably to cash deals. With cash deals the buyer takes all of the risk and enjoys the reward, whereas with a deal with stock, a buyer shares the risk and reward with his investors while also diluting them. However, there might be good arguments for buyers to use stock because of the size of the transaction or for tax reasons.

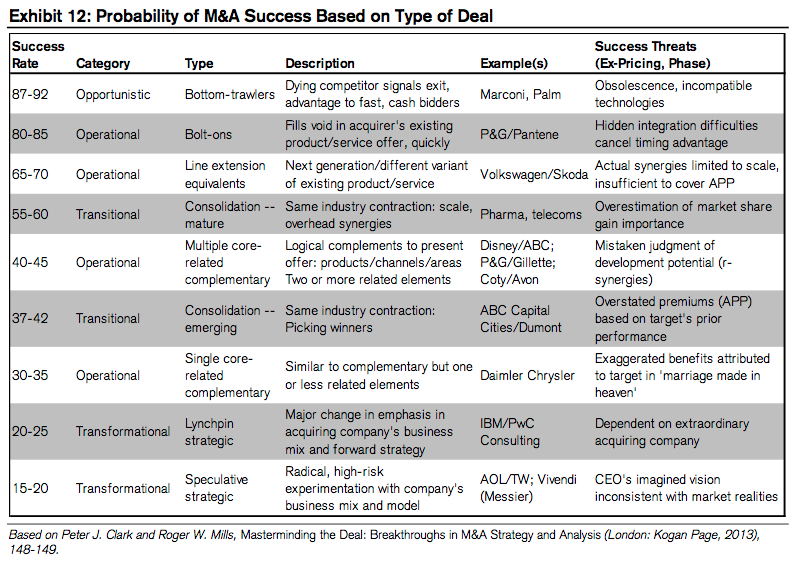

4. Which Strategic Category does the Deal Fall Into?

Conclusion

As we saw in this article, generating value from M&A is challenging. The article can be summed up by the following points:

- M&A requires payment up front for benefits down the road.

- Managers of the buying firm tend to think that they can manage the assets of a target firm more efficiently than the current management. This creates bidding wars and push buyers to overpay.

- Companies tend to overestimate the value of synergies. Companies can generate value by focusing on cost synergies which are more reliable than revenue synergies and by having a clear execution plan to achieve the synergies during the integration.

- When the premium is too large, it’s hard for the buyer to recoup its investment, because the buyer will only create value when the synergies it realizes exceed the premium paid.

- Competitors can replicate the benefits of a deal with internal resources or by cost-cutting accordingly. They can take advantage of the lack of focus as the companies go through the integration process.

- M&A deals are generally costly to reverse. Knowing in which strategic category the deal fall into and choosing the right financing mix is key to determine the success rate of the M&A.